I was watching Episode 42 of the Pickleball Effect podcast while assembling SW1s today, and Braydon asked if it was possible for twistweight to be too high. He went on to mention that he felt that a high twistweight slowed down the acceleration of his backhand flick. I’m a bit surprised that he was able to notice it, but that is an expected effect of higher twistweight.

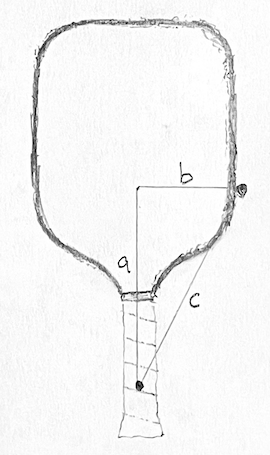

Consider mass added at the 4 and 8 o’clock positions of a paddle and reference the sketch below. The effect of that mass (m) on swingweight is m·a². For example, if adding 6 g (3 g per side), and a is 18 cm, then the swingweight will increase by (0.006 kg)·(18 cm)² = 1.944 kg·cm². The effect of that mass on twistweight is m·b², so if b is 9.5 cm, the twistweight will increase by (0.006 kg)·(9.5 cm)² = 0.542 kg·cm².

There is a third axis about which moment of inertia is interesting. This has conventionally been called spinweight, and it’s measured about an axis 90 degrees from the swingweight axis. In the sketch above, it would be about an axis coming out of the screen through the vertex a-c. It’s also the axis you’d get by installing a paddle into a swingweight machine with the paddle face parallel to the ground (more on that after the break). The effect of the added mass on spinweight is m·c². Length c is √(a² + b²) = 20.35 cm, so the added spinweight is (0.006 kg)·(20.35 cm)² = 2.485 kg·cm².

Note that the sum of the added swingweight and twistweight is equal to the added spinweight: 1.944 + 0.542 = 2.486 kg·cm². This will always be the case, assuming a paddle is approximately planar, and is described by the perpendicular axis theorem.

Back to Braydon’s backhand flick, there’s a large component of acceleration about the spinweight axis for this shot. Given two paddles, with everything equal except that one has a twistweight of 6.0 kg·cm² and the other has a twistweight of 7.0 kg·cm², the second paddle will have a spinweight that is 1.0 kg·cm² higher. The difference is there, but it’s small.

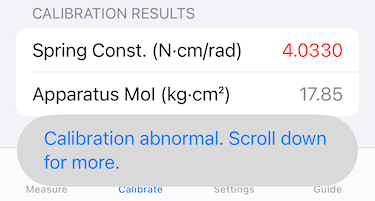

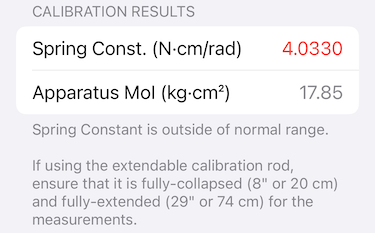

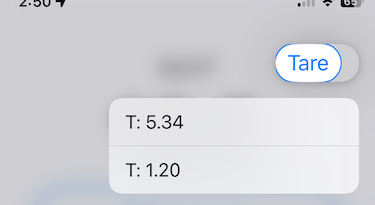

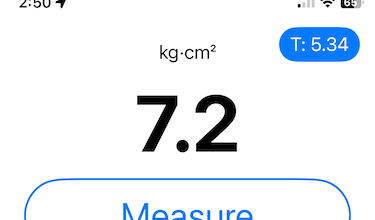

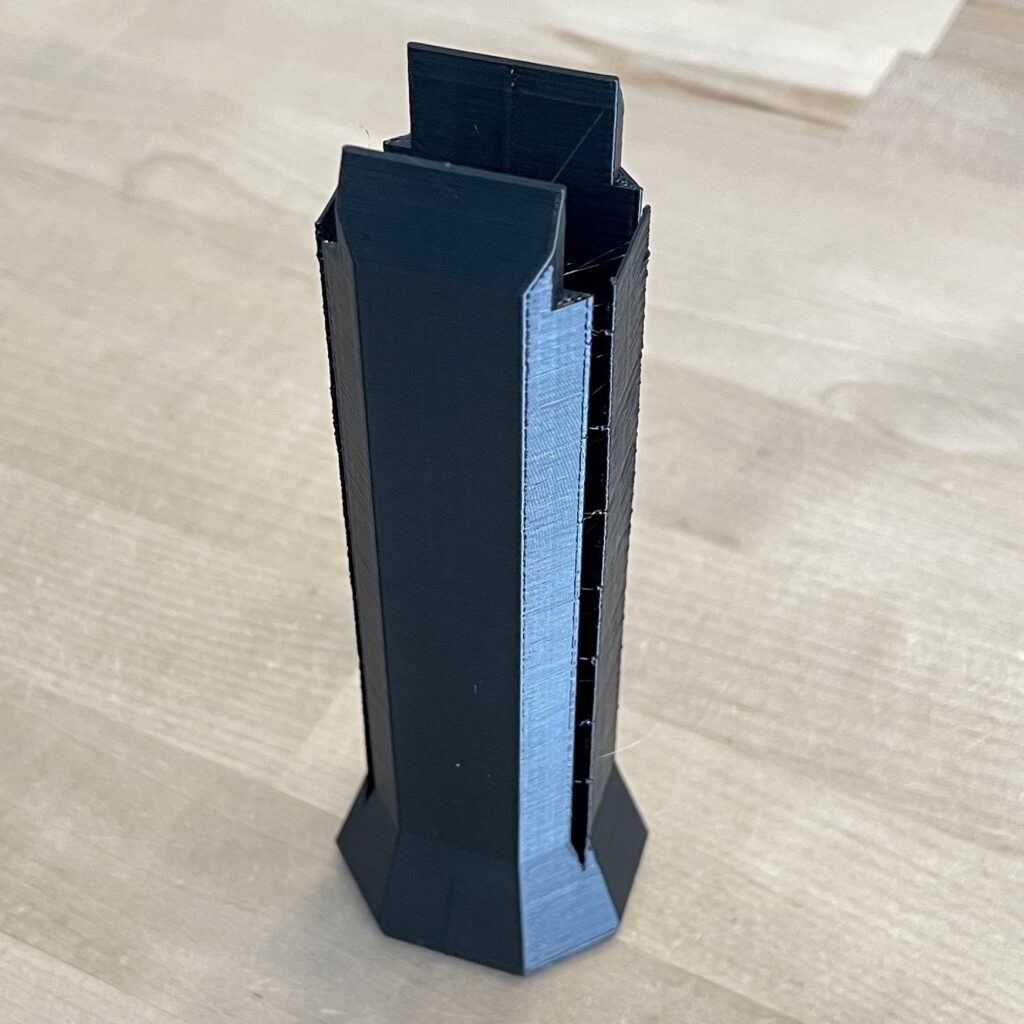

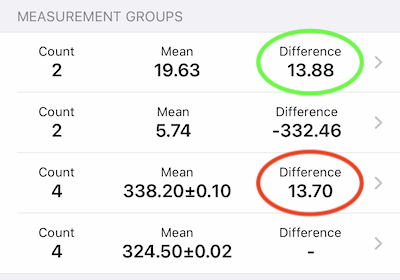

I wanted to add a bit more about measuring swingweight and spinweight in the real world. Theoretically, you could measure both swingweight and spinweight with the SW1. Practically, for paddles, the results are a bit misleading, as the effect of air resistance is very significant in the swingweight orientation. For example, my current main paddle has a swingweight of 114.3 kg·cm² and a twistweight of 7.5 kg·cm², but the spinweight measures 117.7 kg·cm². That’s lower than the expected result of 114.3 + 7.5 = 121.8 kg·cm², but that’s because the swingweight measurement is inflated due to the effect of air resistance. To minimize the effect of air resistance on swingweight, you could measure spinweight and subtract twistweight. In my case, that gives a result of 110.2 kg·cm². Of course, that’s only useful if comparing to paddles measured similarly.

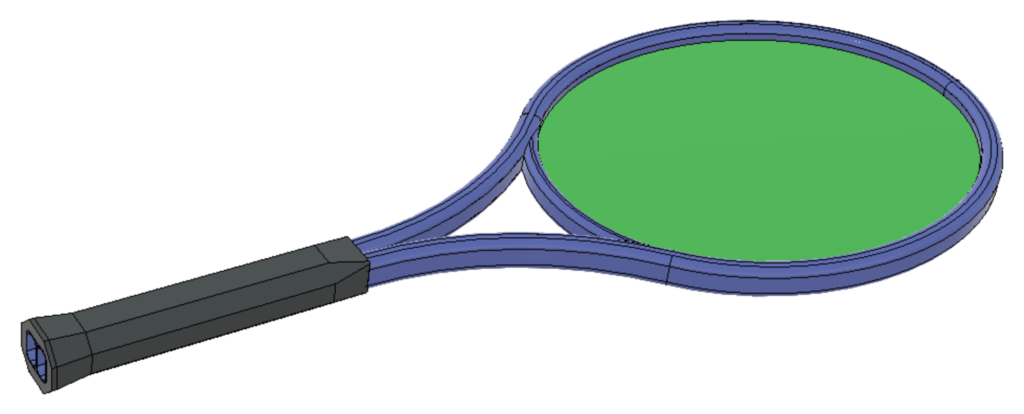

If you’re interested, I have a bit more about the relationship between swingweight, twistweight, and spinweight for tennis racquets in the post Racket Twistweight from Spinweight and Swingweight.